Mexico City, Supreme Court murals

The Supreme Court building in Mexico City is an unremarkable building constructed in 1935, ornate and imposing but as a piece of architecture less grand that its neighbours, the National Palace, and the Cathedral on the other side of the main plaza in the city, Zócalo. At the same time, on its own it signifies power and authority, gravity and, if necessary, force.

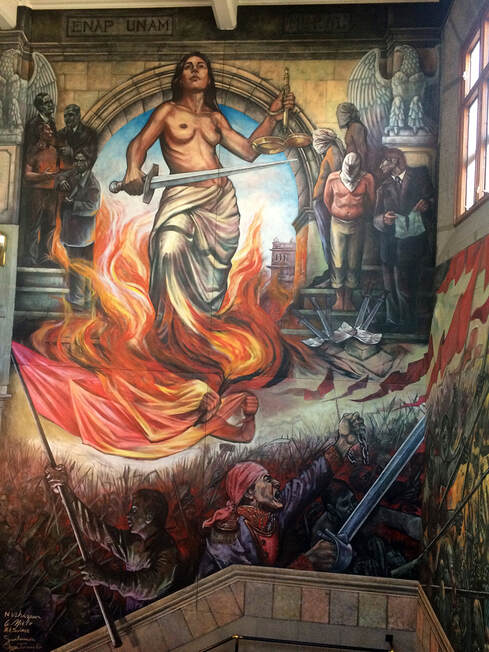

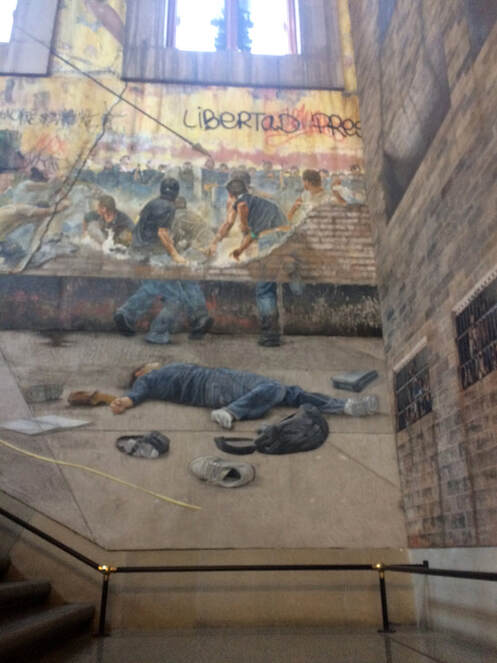

But when one enters the building a different view emerges. Interior murals, two by Clemente Orozco, flank the entrance. At each corner of the building there is a stairwell going from the basement to the second floor, and on the walls of each of the stairwells are murals depicting justice. Or rather, they depict injustice - police torture, the massacre of protestors, people in an overcrowded prison cell. The murals are remarkable in themselves, stark, graphic and haunting. But their site is more remarkable. Why would a supreme court in a democratic state host such depictions of state authoritarianism and crime? What does it mean to walk the stairwells under the eyes of numerous armed police when the walls scream evidence of what policing can mean, and has meant at many periods of Mexican history?

The murals are in effect a kind of morality play. They spell out injustice so that the viewer can hope that the Supreme Court will not allow such things to happen. The trail of injustice goes back a long way; one mural depicts indigenous Mexicans being slaughtered by conquistadors. But there is a sort of teleology involved, because there are also murals pointing to the role of the court in defending the constitution in which the right to justice is enshrined.

The murals were painted by Rafael Cauduro who was commissioned to produce them by Supreme Court judge Jose Ramon Cossio Diaz, one of the youngest judges ever appointed to the Supreme Court. Cossio's liberalism may have given him the edge in seeing through this project in the face of an eleven-person bench not all of whom were as supportive as he. The project was completed in 2009. There is probably no other supreme court in the world that has such murals on its walls.

One mural displays boxes of documents on an office floor, some of which might provide evidence proving someone's innocence. Another shows the ghost of a half-naked woman tied to a chair. Beside her a tattered poster bears the word 'Auschwitz'.

On another wall is a recreation of the massacre of almost 300 students in Mexico City (Tlatelolco) in 1968; towering over the bodies on the ground and the fleeing figures is the turret of a tank. Prisoners, looking traumatized, peer through the bars of an overcrowded cell in yet another image. And at the top of one stairwell an ominous larger than life soldier peers down through a window.

But the most striking images are those showing police torturing suspects. A woman has liquid poured into her nose, a torture known as tehuacanazo. The adjacent mural depicts a man having his head shoved into a toilet by police, a torture known as el poso. The third frame in the sequence is perhaps the most moving of all and shows the end of the conveyor belt of injustice; a woman lies alone at the bottom of a vast well of a cell.

In Chile after the end of Pinochet's dictatorship a truth commission revealed the horrors of torture and disappearance under his watch. The truth commission's report was titled Nunca Mas (Never Again). Mexico had its dirty war as well. Between 1972 and 1978 572 prisoners disappeared while in state custody.

Outside the Mexican Supreme Court on the first Saturday of each month, the Mothers of the Disappeared gather demanding the return of los desaparecidos. In one sense nothing could better display the chasm between ideals and reality. The mothers have not achieved justice. At the same time, it is possible to believe that the murals inside the building where they gather visually convey the same message as Chile's truth commission and thereby hold out some hope that at least future justice can be delivered: nunca mas.

The photos below were taken in March 2018.

Mural in entrance hall of the Supreme Court building.

Genocide of the native populations by the conquistadors.

Justice, backed by revolutionary masses, brings fire and sword, as well as scales, to counter torture and injustice.

Files and the ghostly forms of victims of injustice.

The ghost of a tortured woman.

The massacre of students and others in Tlatelolco in 1968.

The massacre of students and others in Tlatelolco in 1968.

A soldier looks on ominously from a window at the top of the stairwell.

A woman has liquid poured into her nose, a torture known as tehuacanazo.

A man having his head shoved into a toilet by police, a torture known as el poso.

A woman prisoner lies at the bottom of a vast cell.